We may be used to drawing a model under a direct, uninterrupted light source, with the only shadows being those cast by the figure itself. However when other objects are introduced in front of the light source, the model will be adorned by interesting shadow shapes. The most everyday example of this is dappled sunlight coming through the canopy of a tree. The impressionists popularised painting ‘en plein air’ (outside) with a focus on the fleeting effects of light and shadow. This means the shadow shapes would be rapidly changing as they painted, especially in Scotland where you can never count on sunshine! Luckily for us, the effects of sun through foliage can be recreated in the studio with the benefit of a constant light source.

Most essential to representing shadows is tonal contrast. As seen in Anders Zorn’s ‘Nude under a spruce tree’ the shadows can be so large that you start to see light shapes rather than shadow shapes, in the form of chinks of sunlight hitting the body from one side. In this case it may be useful to work on a mid-toned paper so that areas of light can be picked out in white, and the paper left bare to represent the shadow colour, or shaded in black for a more dramatic contrast. The chiaroscuro of natural light seen in Zorn’s work gives an impression of immediacy and spontaneity, rather than that of a scene composed in the studio. Whilst this gives him an affinity with the impressionists, his figures are not just used to reflect the play of light but maintain a weight and corporeality absent from impressionist painting.

When working in colour like the impressionists, close observation of the shadows reveals that they contain a multitude of subtle colours. The impressionists rarely used black in their painting, creating softer shadows than those of Zorn. A fine example of this is Renoir’s ‘Torso, Sunlight effect’. He is quoted as saying “No shadow is black. It always has a colour. Nature knows only colours.” Following the theory of complimentary colours, he adds violet to his flesh tones for the shadows, the complementary of yellow sunlight. As a general rule, shadows contain cool colours whilst the highlights are made up of warmer hues. The deepest shadows, such as under the breasts and below the right arm, are tinged with green and purple. All this colour theory serves to capture the impression of dappled sunlight dancing across the skin.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, ‘Study: Torso, Sunlight effect’, 1876

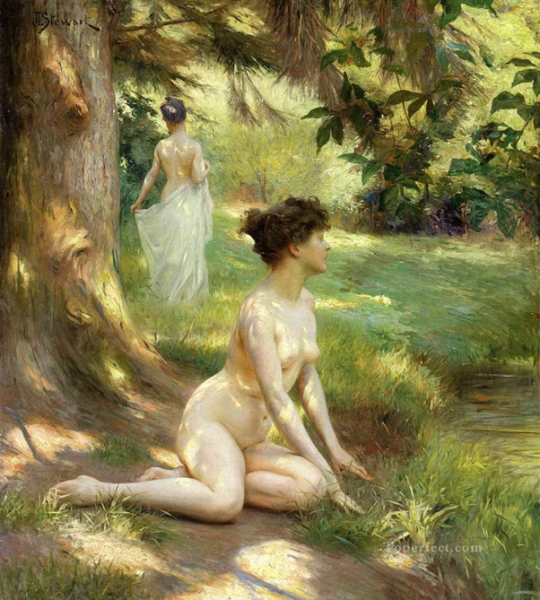

Light and shadow shapes follow the contours of the body and when drawn accurately can help to describe three-dimensional form. Take this advice from Monet; ‘Try to forget what objects you have before you. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape until it gives you your own naïve impression of the scene before you.’ When Renoir’s nude in the sunlight was first viewed, and colour theory was relatively new, she was criticized for looking dead due to the blue-green patches on her body. To avoid your shadows looking like abstract tattoos or bruises on the skin it may be helpful to continue the shapes beyond the figure, onto the floor and walls around them. Julius Leblanc Stewart used this technique in ‘Sunlight’, painting pools of sparkling sunlight on the grass and tree trunks around his figures. This gives a suggestion of the material that the light is travelling through and unifies the scene.

Julius Leblanc Stewart, ‘Sunlight’, 1919