I was recently asked some questions by someone doing their dissertation about body image in relation to modelling. I thought my answers might be of interest to some! For clarity, this is written by Topaz Pauls, not Hayley Whittingham, though the painting below is indeed by Hayley.

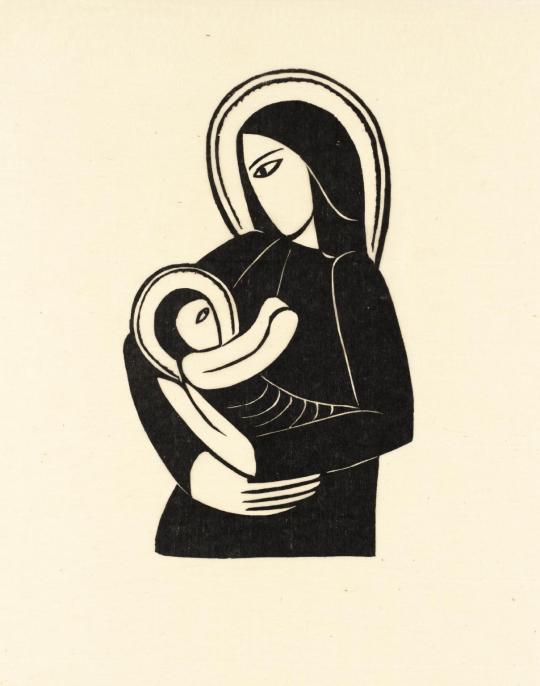

Your Body Is Still A Battleground (2019), by Hayley Whittingham

How did you get into life drawing?

I was lucky enough to be offered life drawing in sixth form. I found it a great way to boost my portfolio; I produced a huge amount of work. This followed on from a GCSE self portrait project where I photographed and then painted myself. At A-Level I created work based around the body, using photographs my friend took of me to paint from. That was my first experience of modelling nude for art – albeit my own. When I moved to Edinburgh for my linguistics degree I took up modelling as a supposedly radical reinvention of myself, taking power over my image by showing it willingly, which til that point I had given others the power over (bullying, feeling self conscious). I realised my body had expressive abilities that were valued and appreciated by others – that went far beyond its mere appearance. And my journey began there.

What was your first life drawing experience like?

I remember the boy next to me being very nervous- I somehow was not. (His nerves disappeared within about 5 minutes.) The model we had was cool as a cucumber which helped. I was both fascinated by her body and admiring of her shamelessness.

How does it feel to be naked in front of people you don’t know?

I only occasionally remember that I am naked, and I am surprised at myself for about a minute. Then I remember that if one can get used to being naked in front of strangers, one can get used to anything.

Does it affect your feelings towards your body?

Yes. I’ve done this for over 10 years if you count my A-Level modelling, and for 8 years as a professional life model. In that time I have gradually realised I don’t care what other people think about my body. I care what I think; that’s different. I know when I am ‘the best version of myself’ and when I’m not. Only I judge that. I was severely bullied in school and still don’t think of myself as ‘beautiful’ even if people tell me I am. Nowadays almost look at myself as if from an artist’s perspective – observing but not judging. There’s no point wishing my body were different. It serves me well and I am grateful it enables me to do the work I do.

Does it empower you?

In terms of what I said above, yes. If my nudity is about choice, then yes. Choosing to be looked at, to show what is supposedly myself at my most vulnerable. However, I feel very detached from any images of myself, mostly because if I felt attached I would judge myself through them – and they are so warped – I am depicted as a zombie, old lady, masculine, thin, fat.... - that I cannot use them to judge myself as they are so unreliable. Every image created is different because every pair of eyes that sees me is different. Every artist has their own lens, and even an individual’s way of seeing changes over time.

That detachment means that perhaps I value my nudity less. I say yes to projects that don’t always appeal to me artistically. Supposedly I am an exceptional model with unique abilities and energies to impart. If I believed what people said about me I would be a huge narcissist. Therefore I don’t charge as much as I could, I am not very selective about who I work with. Is that empowering? It’s a balance I am only just beginning to explore.

Do you think young people would benefit from life drawing? In terms of body confidence/ desexualisation of the body?

OMG YES. It allows you to see bodies of all shapes, sizes, genders, ethnicities, and view them and accept them as they are and not judge beyond that. The act of observing and drawing is an acknowledgement of the forms you see in front of you (notwithstanding your unavoidable personal interpretation of them!). An implicit part of life drawing is that there’s a relationship of trust and gratefulness between the artists and models. They as models are trusting and feel safe enough to show themselves as they are. Reduced to one’s naked form it’s impossible to pretend that you’re something you’re not. Without clothes, without (most) embellishments (like jewellery), all you have is your body and its capability to express who you are at that moment and who you have been up to that point in time. How you move in the world reflects how your experiences have created a certain way of inhabiting your body. And have perhaps left physical marks on that body. As artists we are grateful to be shown this bare authenticity, to be invited to interpret it artistically. There are no words, no explanations given – it’s shown visually and energetically. All this goes far beyond sexualisation – that's only one aspect of possible physical and energetic expression. That’s not to say you can’t acknowledge (to yourself!) that you find the body in front of you sexy. But you also know that sexiness isn’t the point of them being in front of you. And you very quickly move on to appreciating far less superficial things than rating the attractiveness of someone you don’t know.

Do you think life drawing helps people appreciate the body in a different way?

As countless models and artists will testify – the thing that one person likes less about themselves is often the thing that makes them unique. To draw those things is to acknowledge those things. For a model to see them drawn can be cathartic. Someone else has seen ‘those things’ (whatever they may be), and drawn them, acknowledged them, spent time with them, appreciated that they afforded an opportunity to observe something new in the world. And the world hasn’t ended. And those ‘things’ are still there. If we were all the same image of idealised perfection, people would be a lot less interesting – there would be less to observe – to acknowledge, to grapple with, to accept, to appreciate.

What do you think about censored imagery on channels like Instagram?

Platforms like Instagram are very hypocritical. Whilst allowing photoshopped, societally conventionally beautiful supermodels in hypersexualised miniscule coverups, it censors the bodies of the ‘everyday person’ and of their art. Doing so narrows down the range of bodies and expressions that can show themselves to the world. And as mentioned above, to show yourself is a choice, is an act of taking power, to be seen, acknowledged, and be accepted for what you are, and by doing so accept yourself all the more.

What’s the main reaction to your job role?

Sometimes I dread getting out of bed. But not because I don’t want to do the job I do – only because it’s tiring and I’d rather sleep more! I find my work highly meaningful. I enable art to be created, whether as a model or events organiser. Creativity is an incredible way to get to know ourselves, push ourselves, find new boundaries, surprise ourselves, make ourselves proud. Self expression could not be a more purely personal journey. Knowing ourselves better can only lead to happier societies as we discover our very own inner worlds. The only way to discover strengths and abilities we never knew we had, and to begin appreciating them, is through creativity. Then we can discover what we truly want for ourselves – a greater awareness of what our uniqueness can offer the world, and the autonomy and faith in ourselves to pursue that givingness.

How do you think art differs from other aspects of life in terms of the way we view the body?

Art is ESSENTIAL and yet it is not. It feeds the soul but not the body. To feed the body we need to work. To have the energy to work we need to feed the body. This is a purely physical process. What about motivation to work? This involves the soul. To have the motivation to work to feed our bodies, our work needs to feed our souls. Whatever body we have, it has the ability to enable us to be creative in the world in some way. And this is art - in whatever form it may take, using our personal capacity for interpretation to make intentional changes in the world around us – whether that’s cooking dinner or painting in oils. And this creativity is what feeds the soul. And this gives us the motivation, the energy to work, to feed the body, to maintain the circle during our lifetimes.

I feel that we have mostly forgotten that our bodies are vessels of creative potential. Art reminds us of this.

How do you feel when you are drawing/painting?

Only very occasionally do I feel like I have created something beyond myself. It is mostly a slog where I am dissatisfied with the outcomes I have created and therefore dissatisfied with my own self. Yet, I continue, I do it anyway, even if it all ends up under my bed, unseen by the world. I discover aspects of myself I would not have known otherwise. Through my art I discover what kind of lens I’ve got in at the moment. It’s a dialogue between what I am choosing to see and what is presenting itself to me to be seen. I feel I have the duty to hone my technical abilities to represent what sits in between those two things – what presents itself, and what I choose to see. In a way, the art that emerges is a physical manifestation of that lens, and through seeing it physically, I can explore what’s helpful or not to accept as permanent, and what’s helpful to explore changing.